Story of Maria Vincencová, who saved Maria and Imrich Spitzer.

Irenka Foltánová

Irenka was born in 1931 in France, where her parents Maria and Tomas Rosenberg migrated for work. They brought her back to her grandparents in the village of Prestavlky. She was really small then, she doesn’t remember how old she would have been. She only remembers fragments from that period: staying at home, her grandparents going to work in the field, being left to fend for herself. Like a village child.

In 1935, Maria Rosenberg came home to give birth to her second child, a daughter. She took the two girls back to France with her. Before even turning six, Irena started attending school there, but she couldn’t speak the language. Today, she only remembers a few words. “I was such a good student there,” she recalls. “I regret to this day that we came back.”

When Irenka was eight years old, her mother brought the two girls to her mother and returned back to France. Soon the war broke out and the Rosenbergs tried to arrange having the two children brought to them via the Red Cross, but they were unsuccessful. “So we stayed at Grandma’s,” says Irena. “The grandmother’s last name was Vincenc.”

Maria Vincenc

Maria Vincenc lived in a house on a hill near the church. The house was long and there were five companions in one courtyard. Mrs. Vincenc lived “up top, at the end” in a small bedroom with a small kitchen and barn to raise a pig and cows. The kitchen had a bed and in the bedroom were three or four more beds. The bedroom also fit one table and some closets.

Irenka was the oldest granddaughter of Maria Vincenc. Her sister, two girl cousins, and one boy cousin were all younger. Maria’s youngest son was nine years older than Irenka. Mrs. Maria took care of all the children. When her husband, Irenka’s grandfather died, Irenka was nine. Work in the field was inevitable and Maria Vincenc managed everything by herself. Irenka was helping her. “She was quite the woman,” recalls Mrs. Irenka with tears in her eyes.

There were many people and loads of children living in that courtyard. They had lots of fun. The girls sewed dolls from canvas. There were no other toys at the time.

They used to eat cabbage, beans, soup. Bread was baked once a week, and they baked also some dough in the oven. Milk was churned, producing butter and buttermilk. They would eat only what was grown and raised by them. Shopping in a store was only for petroleum, sugar and salt.

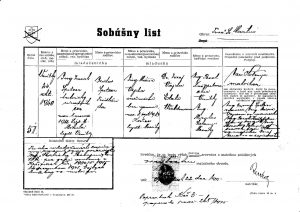

Maria and Imrich Spitzer

Maria Weid and Imrich Spitzer met at high school in Košice. Imrich was a year older than Maria. He received a degree in mechanical engineering in Prague and Maria in chemistry. They studied in the first part of the thirties in the twentieth century. Afterwards, Maria worked in a chemical factory in Usti nad Labem while Imrich probably worked for railways in Slovakia. When the war came, he was exempted as an economically significant Jew. He sent Maria a telegram to come immediately to Slovakia so they could get married thanks to the exemption he had. This would protect her from deportation. He reportedly sent a taxi from Martin to Usti for her. They married in 1941 and lived in Bratislava. They had fake papers, so during the war Imrich Spitzer was called Ivan Sotak and Maria Spitzer was Maria Sotakova. In early 1943, they were imprisoned, but it was likely not because of their Jewish origin, but due to political activity. Imrich wrote letters to Maria from the male ward to the female ward. They were dated from the beginning of 1943 to September of that year. The Spitzers, or during the war, the Sotaks, went to Sered when they left prison.

Maria Weid and Imrich Spitzer met at high school in Košice. Imrich was a year older than Maria. He received a degree in mechanical engineering in Prague and Maria in chemistry. They studied in the first part of the thirties in the twentieth century. Afterwards, Maria worked in a chemical factory in Usti nad Labem while Imrich probably worked for railways in Slovakia. When the war came, he was exempted as an economically significant Jew. He sent Maria a telegram to come immediately to Slovakia so they could get married thanks to the exemption he had. This would protect her from deportation. He reportedly sent a taxi from Martin to Usti for her. They married in 1941 and lived in Bratislava. They had fake papers, so during the war Imrich Spitzer was called Ivan Sotak and Maria Spitzer was Maria Sotakova. In early 1943, they were imprisoned, but it was likely not because of their Jewish origin, but due to political activity. Imrich wrote letters to Maria from the male ward to the female ward. They were dated from the beginning of 1943 to September of that year. The Spitzers, or during the war, the Sotaks, went to Sered when they left prison.

Rosenbergs’ arrival to their home village, Prestavlky

Irenka’s father, Tomas Rosenberg, had to enlist, but he was able to escape. Although he went traveling with his wife Maria, they had to work for some time at estates in Germany. They were digging potatoes and working with beets. They returned home before Christmas. In the winter, Mrs. Irena remembers waiting for them close to dawn. “After that the Uprising happened,” recalls Mrs. Irena, who can’t date the arrival of her parents exactly. According to her data, the Rosenbergs might have come home in late autumn or winter of 1943. Irenka and her sister moved in with their parents. They lived near grandma Vincenc.

The Uprising

When the Uprising broke out, Mrs. Irena remembers the soldiers going from Svaty Kriz to Handlova. People from the surrounding villages came to their village. “There were strangers all over the village,” recalls Mrs. Irena. Their relatives also came to live with them. When they left, some others came. People were walking to and fro. “One of them was pregnant, she even gave birth at our place,” Irena recalls.

Spitzers – escape from Sered and hiding

The Spitzers escaped from Sered in September, 1944. They went into the Uprising and then they hid.

A relative of Mrs. Vincenc by the name of Mrs. Zamora, lived in Dolna Zdana. Mrs. Vincenc simply called her “aunt” and she visited this aunt one night. She took her granddaughter Irenka along. It might have been either September or October, Mrs. Irenka only remembers that it was not raining.

“I went with grandma, I didn’t know where or what for. As we arrived in Zamory, Ivan Skalicky and his wife Maria were waiting there (in the meantime the Spitzers changed their name again – to Skalicky, which they used during the war – they apparently had two cover names, Mrs. Foltan remembers them under this name). They carried a small backpack. They were very likeable people. We walked home with them to Prestavlky. In the dark. Not on the road but through the fields. We brought them to Grandma’s and they stayed there.”

They ate everything that grandma cooked. They walked to the outhouse through the corridor – the manure was nearby.

They slept in the small bedroom in one bed. Mrs. Vincenc gave the young woman some clothes typical of Prestavlky, ‘kytle’. “She could tie up her headscarf so well that no one would ever know she wasn’t from the village. If the Germans found out she was Jewish, they would have shot the whole family, maybe even the entire village like they did in Klak and Ostry Grun,” observes Irena Foltan. Prestavlky was a small village, but there were both camps present.

There were eight people living in the small house. Thanks to the full house, German soldiers did not live with them, though they had horses in their stables. The conditions were dangerous. During nights, there were visits from both the Resistance and the Germans in the village. One day it was Germans, another it was partisans, asking for bread, bacon, warm clothing or long underwear.

Maria was not conspicuous because she was dressed much like Mrs. Vincenc. And she was expecting.

Plucking feathers

It was common to farm geese in the village, and feathers were plucked for bedding in the house where Irenka lived with her parents. Maria Skalicka, who was curious, also went to see it. It was on St. Nicholas’ day. The boys walked about with St. Nick and visited the house. They blew into feathers, and spread around ashes to get the women black. “Even Maria got this experience. She was ‘blackened’”, laughs Mrs. Irenka.

Danger

One night German soldiers knocked on the door of the house where the Rosenbergs lived with their children. They walked in and aimed their machine guns at the children that slept by the door of the house. They were looking for partisans.

The order was issued that men must enlist. Among them was Irenka‘s father, born in 1908. “They were enlisted but the next morning the men came home,” recalls Mrs. Irenka. Bridges were blasted, railway tracks destroyed, they had no way to get to the troops, so they returned. Since then, they had to hide in the mountains though, because Germans were looking for men. Only older men remained in the village. The men had made a bunker out of fir and wood in the forest, in which they lived. They used to come home to secretly get food. Ivan Skalicky, or Imrich Spitzer, used to hide in the bunker as well.

Once the drummer drummed that the Germans were going to walk through the woods. “Usually, the Germans did not go into the woods because they were afraid. They just patrolled under the mountain,” recalls Mrs. Irenka.

Her father sent Irenka to go in the woods to tell the men what was going on. “I took a friend to come with me,” remembers Irenka. At the same time, Ivan went to see the men in the woods as well. Irenka called to him and waved her scarf. But he was too far away to hear her. At one of the houses on the hill, German soldiers were on patrol and when noticing the girls, they wanted to shoot at them. The man who lived in the house prevented them from doing so. Ivan entered the forest and Irenka returned home.

“Those men stayed there for a long time. They kept a guard. One night the man on guard fell asleep, so the shed caught on fire. After that, the men moved back home and each was hiding wherever they could.”

Irenka‘s father had a shelter under the wood-house. Every evening he bundled up well and walked in. They camouflaged the bunker from the outside. By then, Germans also lived in the house where Irenka lived with her parents. First, only the “officer” himself, later there came more, and eventually the yard was full of horses. The Germans slept in the bedroom and the family squeezed in the kitchen. They had a kitchen in the neighborhood for the troops, and the girls, including Irenka, used to go “bleach potatoes” for them. They also washed their clothes.

Some German soldiers spoke Czech and wept whether they would ever see their family, and how they would get home… “It was terrible. After all, it wasn’t their fault that they had to go fight. Whether they were Germans, or anybody else… But there were all sorts among them, too.”

One of the soldiers was constantly spying around. The family had a bedroom, a kitchen, and a pantry that was a meter wide. From the outside was a window that Mrs. Irenka’s father bricked over and painted. That’s where they kept the food, clothes, and shoes. From the kitchen, the door was camouflaged with cupboards. This soldier walked around the yard and calculated that a meter was missing somewhere. “But then he had to go to the battle and it was said he died. Thank God!”

Trenches were also dug above the village. If someone were to reveal that Mrs Vincenc was hiding Jews, no stone would be unturned.

The end of war

The Spitzers lived with Mrs. Vincenc until the end of war. They lived in very modest conditions. Maria is also remembered by Mrs. Vincenc’s cousin from Humenne. Once some German soldiers walked through the village and Maria grabbed her and hid her in a straw basket under some hay, hiding there herself and waiting for them to pass along.

When the Germans left, everyone sighed with relief. They were in the village for two weeks and then had to retreat. There was no fighting in the actual village, only once a bomb was thrown up over the mountain, so the place is called Bomb Pit to this day.

Shoes

When the war ended, Ivan possibly had to go to Košice himself. Mrs. Irenka’s father had nailed many nails into his soles to make the shoes last as long as possible. The trains were not in service so he had to walk. Later, Ivan informed them that the shoes really lasted a long way.

Life after war

After the war ended, Ivan and Maria left for Bratislava, where their first daughter Katarina was born and later, her sister as well. For some time, they lived in Prague and then in Bratislava again. Once, Skalickis invited Mrs. Vincenc to Prague for “Spartakiada”. Katarina was studying by then. She remembers a very energetic lady that came dressed in folk wear.

Her parents didn’t talk much about war and Prestavlky. Mrs. Katarina, however, discovered their fake papers once and she began investigating. All she knew was that her parents were hiding after the Uprising. She didn’t know the reason. And it wasn’t until she was 15 years old, that she learned she was a Jew.

However, the couple used to mention Mrs. Vincenc frequently. They wrote letters to her at Christmas. And they would send packages to each other. Mrs. Katarina remembers that once a package arrived with lard and goose inside. It was no good anymore so they had to throw it away.

When Mrs. Skalicka died in 1953, Mr Skalicky remarried, and both girls emigrated abroad in 1969, Anna is in England, Katarina in Germany.

They didn’t speak about war in Prestavlky

There was no mention of how Mrs. Vincenc’s family was hiding the Jewish couple in Prestavlky either. Mrs. Foltan thinks that no one in the village even knew that the Jews were hidden in their house.

Only a few years ago, Mrs. Vaniš asked her if it was really true that a Jewish couple were rescued by them.

“It’s true, I told her, Valika, it’s true. Well, I guess nobody will kill me anymore for being the oldest granddaughter,” says Irenka.

Renewed contact after years

In 2007, after many years without any contact, Mrs. Katarina Reckers took a trip to the village of Prestavlky.

“I had it in my head continuously. I knew about the fake papers, and I wanted to investigate for my two sons’ sake. So I told myself, let’s go and see.”

She knew Mrs. Vincenc was no longer alive, but she had no idea whether they would find any of the relatives. They met an elderly lady on the street who immediately referred them to Mrs. Foltan. They rang her bell and said they were daughters of Imrich and Maria Spitzer. Mrs. Irenka immediately knew who they’re talking about.

“When they came here, my husband was sitting here on the bench in the courtyard, and she says ‘I was conceived here.’ I started crying, it was a meeting that you can’t ever imagine. I understood right away who they were and what they were looking for. It was true joy!”

Katka and Anna, the sisters, came. Their mother died at 41. They were curious and asking about everything.

“I will never forget that, even after I die, I will always remember it there,” conludes Mrs. Foltan about the first meeting with Mrs. Katka and her sister Anna.

Katarina Reckers feels they have met a loved one because they had a past here that connected them. It was very emotional for the two of them also, because after so many years they found someone who had experienced a war and knew their parents.

Grandma

When the name Maria Vincenc is mentioned, it means “grandma” to Mrs. Katarina.

That’s how they referred to her in their home.

Katka and Anna had no grandparents as children and Grandma Maria Vincenc was the only “grandma” for them.

“Were it not for ‘grandma’, I wouldn’t be alive either,” said Katarina Reckers.

Mrs. Foltan, who is 87 years old, also considers her grandmother’s action as right. Looking at her photo, she says she resembles her…

“I think she had an endlessly good soul.”

Comments are closed.